The Trinity for Newbies: One Theologian’s Guide to Knowing God

February 9, 2021

Believing in and knowing the Triune God is what makes Christianity, well, Christian. In other words, a Trinity-free Christianity isn’t Christianity—it’s something else entirely.

But there’s a problem: the Trinity is one of the most mysterious and difficult doctrines in all of Christianity. It doesn’t make sense to us.

How can one God be three persons?

How can each be fully God, yet the Father isn’t the Son, the Son isn’t the Spirit, and the Spirit isn’t the Father?

How can Jesus be both God and man?

These aren’t new questions—and thankfully we have old answers for them.

If we want to know more about something as profound as the Trinity, where do we start?

Theologians smarter than us helped answer them long ago, and one of them was a guy named Gregory from a small village named Nazianzus (modern-day Turkey). He helped write the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which codified some of the early Christian language about the Trinity.

Gregory gave five “theological orations,” or speeches, sometime around AD 379–380. They have cemented their legacy as one of the clearest explanations of the doctrine of the Trinity and he begins in this way: “We need actually ‘to be still’ in order to know God.” [1] Even someone as smart as Gregory understands that before we dive into discussing the Trinity, we need to consider the weight of what we are doing. Talking about the Trinity is not a proving ground for scholastic acumen or writing ability—it’s an act of worship from a posture of humility. We need a “continual remembrance of God,” including His glory, His greatness, and His character.[2] To forget our humanness and forget God’s “God-ness” is to get the Trinity wrong for the get-go.

Below is an overview of Gregory's many contributions to theology. A lot of these points have been condensed from his Five Theological Orations to help make it more accessible.

So, let's see Gregory's guide to knowing God.

God’s self-revelation starts with the economy

For Gregory, God's revelation starts God's self-revealing. We can think of it this way: because God is God, there is a wide gap between Him and us. This gap is so big that we can only know God if He reveals Himself to us. Because we are created (or because we are “not-God”), we are unable to discover God apart from His free act of making Himself known to us.

God is completely transcendent.

He is totally “other” than us.

He is, well, God.

This is called the doctrine of revelation: God must reveal Himself to us in order for us to know Him—otherwise we would be so blinded by our sinfulness and our human nature (our “not-God-ness”) that we could not even acknowledge Him.

In order to know God at all, we must be entirely dependent on God making Himself known to us. God gave us creation to reveal Himself (Rom. 1:20, Psalm 19:1–4). God gave us the Scriptures to reveal Himself (2 Tim. 3:16, 2 Pet. 1:21).

The most concise way God reveals Himself to us is in the gospel: God reveals who He is through the acts He does. In other words, we most clearly understand the Trinity when we understand the way God works in salvation, because that is the way God has chosen to reveal Himself.

Early church theologians called this the economy of God: the acts of God in handling our sinful state. The Greek word “economy” was typically used to describe how one handled or stewarded their household, and when we look to the gospel story, God “handles” humanity’s sin problem by becoming man and bearing the punishment we deserved. Thus, economy. Christ defeats death through his own death, and by the Spirit we are united with him in his resurrection. You can think of the economy of God as “the plan of salvation where God chooses to identify and reveal Himself.” It is through this plan that God intends to communicate things about Himself.

Paul writes this economy into Galatians 4:4–7: “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’ So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God.”

We could summarize what these verses say like this: “God who is Father, Son, and Spirit has reached out through the Son and by the Spirit to embrace us as sons and daughters.” In the economy of God, who God is always relates to what God does. So, when we think deeply about the three Persons of the Trinity, we must consider what each does.

So, what does this mean? Well, for starters, you probably know more about the Trinity than you are giving yourself credit for! If you have professed faith in Jesus Christ as your Lord, the Spirit has worked in you so that you can know the Father.

You may not have been able to put it into words, but your faith means you’re already participating in the most wonderful work in the economy of God: salvation. Every time you conclude a prayer, “in Jesus’s name,” or “in Christ’s name,” you’re approaching the Father through the Son according to the Spirit in you. He is interceding on your behalf before the Father!

So, first things first: we read “from economy to theology.” What is revealed to us is how we know things about God. We may not make complete sense of it—in fact, we won’t: it’s a mystery that only God Himself can fully comprehend. But we know it’s true.

God’s self-revelation reveals one God in three distinct Persons

There are two fundamental and related confessions about the Trinity: God is “one essence,” and God is “three Persons.”

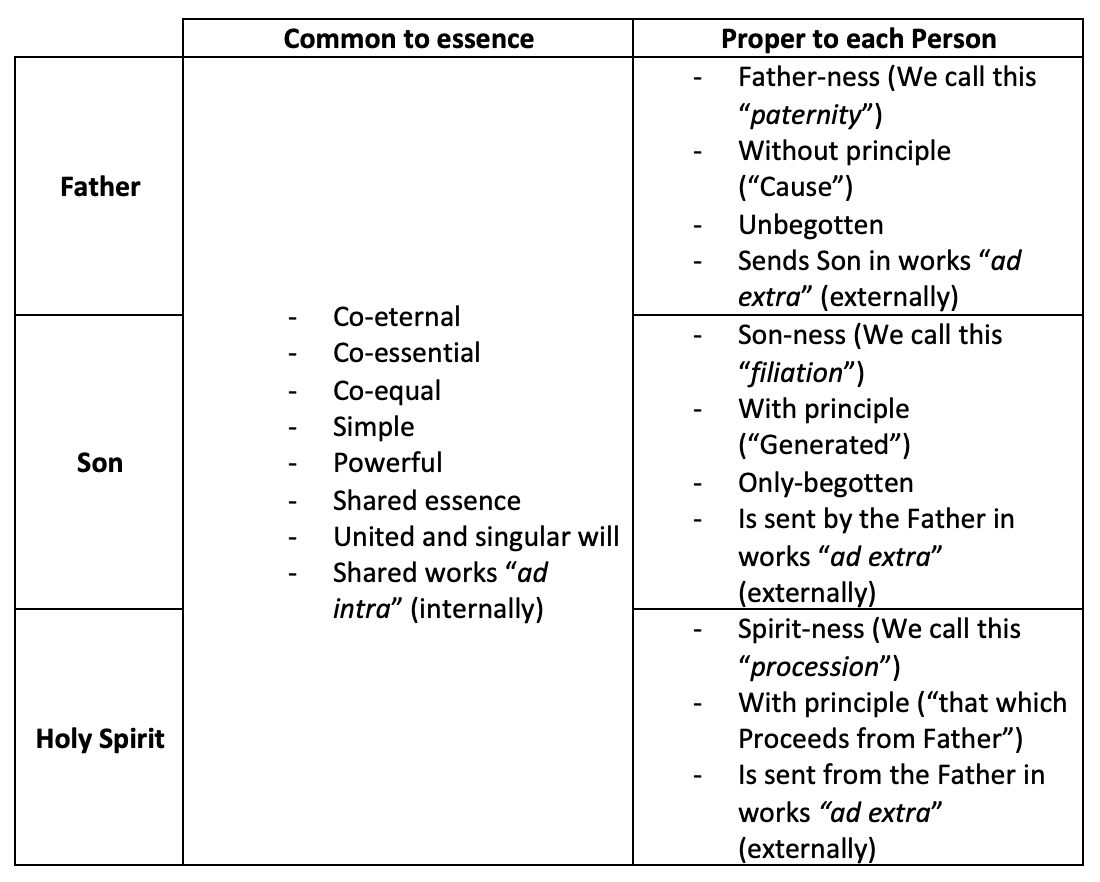

There are traits that are shared (common) and traits that belong to only one of the Persons in God (proper). Imagine looking at God as the Trinity through a pair of theology glasses. The “one essence” lens sees and describes what is common to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The “three Persons” lens sees and describes what is proper to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The chart below helps give an overview of some of the terms typically associated with this idea.

I know—chances are you haven’t heard most of these words in church before. Here’s the main thing that we need to take away from God’s revelation of Himself as one God in three Persons: the Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Spirit, the Spirit is not the Father—yet all three of these share a common, divine essence.

The Father is uniquely Father, the Son is uniquely Son, and the Spirit is uniquely Spirit. This has always been true, because in order for the Father to be the Father, he had to have been “fathering.” He had to be begetting the Son. In order for the Son to be the Son, he had to be “begotten.” In order for the Spirit to be the Spirit, he had to be “proceeding” from the Father and the Son—because he isn’t the Father or Son. This all had to be taking place in eternity past in order for any of them to be who they are. [3]

Even crazier: none of this changes when Jesus is born as a man. Jesus didn’t “become” God. Instead, at his birth, Jesus united in himself his divine nature with his human nature. The incarnation is an “addition by subtraction,” a self-emptying so that the Son could save humanity.

Consider Jesus, who, “though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” (Phil 2:6–11).

One God, three Persons; one Jesus, two natures; one economy to save God's people.

A final note on the Son being sent

I wanted to add a quick clarification here, because I want to make sure I don’t cause more questions than answers. When something begets (or parents) an offspring, the offspring must necessarily share in the nature of its parent.

For example, when a dog begets a puppy, that puppy shares in its father’s ‘dog-ness.’

It can’t be an ostrich.

It can’t be a lion.

It must be a dog. It must be a dog because it must share in the nature of its parent. The puppy now embodies the very nature of what it means to be a dog.

The same idea can be applied to our understanding of how the Son can be generated and yet not lesser than the Father in divinity. The Father and the Son are both fully God because their very essence consists of everything it is to be God. If we understand the Father’s nature to be “what it means to be God,” then the Son must share in this—the Son must also be “what it means to be God.”

The Father being considered the “principle” or “beginning” of this order is called the divine taxis. (Taxis is just a fancy Latin word for “order.”)

While all three Persons are equally God, there is an order in the Trinity.

The Father is the one who does the sending, and the Son is the one who is sent. However, this order does not entail superiority or inferiority. The Son is not less divine than the Father just because he is sent; in fact, quite the opposite: since he is begotten by the Father, he shares in the very nature of the Father. Thus, the Son is equally God.

The doctrine of the Trinity is one of the most important and equally understudied doctrines in the church today. I pray that FBA would rise to the challenge of being a congregation that seeks to know God more deeply—even when it's hard—in hopes of growing in holiness. (And, of course, you are free to reply to this with questions via email or online!)

[1] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 27.3.

[2] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 27.4.

[3] Gregory talks about this in the beginnings of Oration 28.